Lasting from Palm Sunday (Domingo de Ramos) to Easter Sunday (Lunes de Pascua) , Semana Santa (Holy Week) is the most important annual cultural and religious event in Spain.

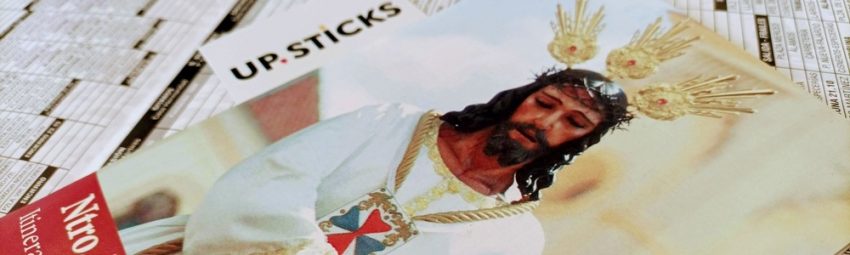

Although each Spanish region, and even city and village, has its own customs and practices for Easter, Andalucia takes top spot for spectacular processions. Sumptuously decorated statues (pasos) on elaborate, candle-filled floats (tronos), surrounded by rows of penitents (nazarenos) in pointed head dresses (capirotes), black-clad ladies in lacy mantillas and backed by a hypnotic drumbeat that almost makes it seem like the floats are swaying in time to the music.

But as impressive as these displays are, there’s a lot more to Semana Santa in Spain than meets the eye – find out more!

Why do they wear pointy hats?

For some reason, the pointy hat discussion raises its head every Semana Santa. One theory is that the pointy hats (capirotes) have their origins in the Spanish Inquisition, when convicts were paraded through the streets of their town as a penance, wearing coloured conical hats to indicate the crimes they were charged with. Over time, the hats changed to cover the face as well (so offenders could keep their anonymity) and grew in height as a way of drawing attention to God, rather than the wearer. Over time, the conical headdress became associated with penitence and was adopted accordingly by the Catholic Church in Spain.

Who wears the pointy hats?

That would be the Brotherhoods. The Brotherhoods are part of the fabric of life in Spain – every family is part of one. They ARE Semana Santa; responsible for organising, financing and delivering the whole shebang, along with countless other social, cultural, religious and traditional celebrations.

Emerging as early as the 14th century and affiliated with their local Catholic Church, the Brotherhoods (‘cofradias’ or ‘hermandades’ in Spanish) are religious and social groups of local people, focused on community good works and maintaining traditional values. Back in the day, a cofradia was a sort of professional “guild”, for example Fisherman’s Brotherhood (Cofradia de Pescadores) while a Hermandad had members from all sorts of professions, trades and backgrounds. Over the years, the cofradias and hermandades have become pretty much the same thing, with the distinct naming kept for traditional reasons.

So why processions – what does it all mean?

The spectacular processions are “living theatre”, with every element carefully designed to tell the story of the Passion (Christ’s death and resurrection). It’s not just visual either; as a way to pay homage to the pain that Jesus went through, some penitents walk in bare feet, the man chosen to play the role of Jesus normally drags a heavy wooden cross and the floats are carried on the shoulders of “costaleros” – all this for anywhere between 6 and 14 hours, depending on how long the procession takes. It’s no wonder that some hospitals open specialist “costalero units” during Easter week. The costaleros train all year to make sure they all move in perfect sync, which is no mean feat when you see the size of these statues and the frames they’re carried on (some can weigh up to a tonne!).

What’s the best way to watch the processions?

If all that sounds rather exhausting, spectators have a much easier time of it. In Seville or Malaga you can book seats with the Brotherhoods, reserve a hotel room on the route or if you’re really lucky, you’ll know someone who has an apartment with a view. Be warned, it’s not cheap and you’ll need to book early. It’s also incredibly crowded – don’t try and drive into the city, take public transport and follow the signed “pathways” to walk around. All the local newspapers will publish daily itineraries and maps, so our top tip is to find yourself a bar or restaurant on the route, settle in for the night and soak up the atmosphere.

Although cities get all the attention, the essence of authentic Spanish Semana Santa is more often found In the smaller towns and villages, some of which have processions that are classed as “Special Interest Events”.

Due to the central role played by the Brotherhoods in the day-to-day life of many Spaniards, the whole town is involved in some way with Semana Santa, and there really is nothing quite like it.

During the afternoon of a procession, families gather in large groups, all dressed up to the nines, chatting, laughing, playing – telling anyone who’ll listen about how their son is a costalero this year (big honour!) or chuffed to pieces that their granddaughter is playing in the band. Rows and rows of chairs line the streets, with the youngest or the oldest sitting at the front, and under every other seat is a huge bag filled with supplies for what can be a long wait. Gradually the streets fill up, until it’s standing room only. Then a deep-toned hand bell tolls twice, there’s a waft of incense and the marching band trumpets and drums strike up. Here it comes!

It’s not just processions, there’s plenty more to do at Easter in Spain

If you are in the Mijas Pueblo area, kids will love making their very own Easter Eggs at the Mayan Monkey chocolate factory on the main square, or get crafty with the Lions Club Easter Bonnet parade (remember those?) in La Cala de Mijas.

If running is your thing, then most areas hold an Easter event, which you can find here.

Sustenance for Semana Santa – Easter foodie treats

While you’ll find chocolate Easter eggs pretty much everywhere, there are some delicious Easter cakes and pastries too; be sure to try at least one Torrija, buñuelo de viento, or pestiño

If you don’t have a sweet tooth, then why not sample cod croquettes (croquetas de bacalao) or bacalao pil-pil for something completely different.

And finally …

One of the most unusual Easter traditions can be found in Malaga, where in honour of the Wednesday procession of the brotherhood of Nuestro Padre Jesus El Rico, a prisoner is pardoned and released from jail. Originating in 1759, all the info on this year’s “winner” can be found here.

The information in this article was current on the date published.

Article last reviewed 05.08.2022